62. The Income Fluctuation Problem IV: Transient Income Shocks#

GPU

This lecture was built using a machine with access to a GPU — although it will also run without one.

Google Colab has a free tier with GPUs that you can access as follows:

Click on the “play” icon top right

Select Colab

Set the runtime environment to include a GPU

62.1. Overview#

In this lecture we continue extend the IFP from The Income Fluctuation Problem III: The Endogenous Grid Method by adding transient shocks to the income process.

In addition to what’s in Anaconda, this lecture will need the following libraries:

!pip install quantecon jax

We’ll also need the following imports:

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import numpy as np

import numba

from quantecon import MarkovChain

import jax

import jax.numpy as jnp

from typing import NamedTuple

62.2. The Household Problem#

We briefly outline the model and then discuss how to solve it.

Readers seeking a more extensive discussion of the model and the EGM solution method can review The Income Fluctuation Problem III: The Endogenous Grid Method.

62.2.1. Set-Up#

A household chooses a state-contingent consumption plan \(\{c_t\}_{t \geq 0}\) to maximize

subject to

The definitions of symbols and the timing are the same as in The Income Fluctuation Problem III: The Endogenous Grid Method.

Now, non-capital income \(Y_t\) is given by \(Y_t = y(Z_t, \eta_t)\), where

\(\{Z_t\}\) is an exogenous state process (persistent component),

\(\{\eta_t\}\) is an IID shock process, and

\(y\) is a function taking values in \(\mathbb{R}_+\).

Throughout this lecture, we assume that \(\eta_t \sim N(0, 1)\).

We again take \(\{Z_t\}\) to be a finite state Markov chain taking values in \(\mathsf Z\) with Markov matrix \(\Pi\).

The shock process \(\{\eta_t\}\) is independent of \(\{Z_t\}\) and represents transient income fluctuations.

In addition to previous assumptions, we suppose that \(y(z, \eta) = \exp(a_y \eta + z b_y)\) where \(a_y, b_y\) are positive constants

The asset space and state space are unchanged, as is the definition of an optimal path.

The functional Euler equation has the form

Here

\((u' \circ \sigma)(s) := u'(\sigma(s))\),

primes indicate next period states (as well as derivatives),

\(\phi\) is the density of the shock \(\eta_t\) (standard normal), and

\(\sigma\) is the unknown function.

The equality (62.2) holds at all interior choices, meaning \(\sigma(a, z) < a\).

We aim to find a fixed point \(\sigma\) of (62.2).

To do so we use the EGM.

Below we use the relationships \(a_t = c_t + s_t\) and \(a_{t+1} = R s_t + Y_{t+1}\).

We begin with an exogenous savings grid \(s_0 < s_1 < \cdots < s_m\) with \(s_0 = 0\).

We fix a current guess of the policy function \(\sigma\).

For each exogenous savings level \(s_i\) with \(i \geq 1\) and current state \(z_j\), we set

The Euler equation holds here because \(i \geq 1\) implies \(s_i > 0\) and hence consumption is interior.

For the boundary case \(s_0 = 0\) we set

We then obtain a corresponding endogenous grid of current assets via

Our next guess of the policy function, which we write as \(K\sigma\), is the linear interpolation of the interpolation points

for each \(j\).

62.3. NumPy Implementation#

In this section we’ll code up a NumPy version of the code that aims only for clarity, rather than efficiency.

Once we have it working, we’ll produce a JAX version that’s far more efficient and check that we obtain the same results.

We use the CRRA utility specification

62.3.1. Set Up#

Here we build a class called IFPNumPy that stores the model primitives.

The exogenous state process \(\{Z_t\}\) defaults to a two-state Markov chain with transition matrix \(\Pi\).

class IFPNumPy(NamedTuple):

R: float # Gross interest rate R = 1 + r

β: float # Discount factor

γ: float # Preference parameter

Π: np.ndarray # Markov matrix for exogenous shock

z_grid: np.ndarray # Markov state values for Z_t

s: np.ndarray # Exogenous savings grid

a_y: float # Scale parameter for Y_t

b_y: float # Additive parameter for Y_t

η_draws: np.ndarray # Draws of innovation η for MC

def create_ifp(r=0.01,

β=0.96,

γ=1.5,

Π=((0.6, 0.4),

(0.05, 0.95)),

z_grid=(-10.0, np.log(2.0)),

savings_grid_max=16,

savings_grid_size=50,

a_y=0.2,

b_y=0.5,

shock_draw_size=100,

seed=1234):

np.random.seed(seed)

s = np.linspace(0, savings_grid_max, savings_grid_size)

Π, z_grid = np.array(Π), np.array(z_grid)

R = 1 + r

η_draws = np.random.randn(shock_draw_size)

assert R * β < 1, "Stability condition violated."

return IFPNumPy(R, β, γ, Π, z_grid, s, a_y, b_y, η_draws)

62.3.2. Solver#

Here is the operator \(K\) that transforms current guess \(\sigma\) into next period guess \(K\sigma\).

In practice, it takes in

a guess of optimal consumption values \(c_{ij}\), stored as

c_vecand a corresponding set of endogenous grid points \(a^e_{ij}\), stored as

a_vec

These are converted into a consumption policy \(a \mapsto \sigma(a, z_j)\) by linear interpolation of \((a^e_{ij}, c_{ij})\) over \(i\) for each \(j\).

When we compute consumption in (62.3), we will use Monte Carlo over \(\eta'\), so that the expression becomes

with each \(\eta_{\ell}\) being a standard normal draw.

@numba.jit

def K_numpy(

c_in: np.ndarray, # Initial guess of σ on grid endogenous grid

a_in: np.ndarray, # Initial endogenous grid

ifp_numpy: IFPNumPy

) -> np.ndarray:

"""

The Euler equation operator for the IFP model using the

Endogenous Grid Method.

This operator implements one iteration of the EGM algorithm to

update the consumption policy function.

"""

R, β, γ, Π, z_grid, s, a_y, b_y, η_draws = ifp_numpy

n_a = len(s)

n_z = len(z_grid)

# Utility functions

def u_prime(c):

return c**(-γ)

def u_prime_inv(c):

return c**(-1/γ)

def y(z, η):

return np.exp(a_y * η + z * b_y)

c_out = np.zeros_like(c_in)

for i in range(1, n_a): # Start from 1 for positive savings levels

for j in range(n_z):

# Compute Σ_z' ∫ u'(σ(R s_i + y(z', η'), z')) φ(η') dη' Π[z_j, z']

expectation = 0.0

for k in range(n_z):

z_prime = z_grid[k]

# Integrate over η draws (Monte Carlo)

inner_sum = 0.0

for η in η_draws:

# Calculate next period assets

next_a = R * s[i] + y(z_prime, η)

# Interpolate to get σ(R s_i + y(z', η), z')

next_c = np.interp(next_a, a_in[:, k], c_in[:, k])

# Add to the inner sum

inner_sum += u_prime(next_c)

# Average over η draws to approximate the integral

# ∫ u'(σ(R s_i + y(z', η'), z')) φ(η') dη' when z' = z_grid[k]

inner_mean_k = (inner_sum / len(η_draws))

# Weight by transition probability and add to the expectation

expectation += inner_mean_k * Π[j, k]

# Calculate updated c_{ij} values

c_out[i, j] = u_prime_inv(β * R * expectation)

a_out = c_out + s[:, None]

return c_out, a_out

To solve the model we use a simple while loop.

def solve_model_numpy(

ifp_numpy: IFPNumPy,

c_init: np.ndarray,

a_init: np.ndarray,

tol: float = 1e-5,

max_iter: int = 1_000

) -> np.ndarray:

"""

Solve the model using time iteration with EGM.

"""

c_in, a_in = c_init, a_init

i = 0

error = tol + 1

while error > tol and i < max_iter:

c_out, a_out = K_numpy(c_in, a_in, ifp_numpy)

error = np.max(np.abs(c_out - c_in))

i = i + 1

c_in, a_in = c_out, a_out

return c_out, a_out

Let’s road test the EGM code.

ifp_numpy = create_ifp()

R, β, γ, Π, z_grid, s, a_y, b_y, η_draws = ifp_numpy

# Initial conditions -- agent consumes everything

a_init = s[:, None] * np.ones(len(z_grid))

c_init = a_init

# Solve from these initial conditions

c_vec, a_vec = solve_model_numpy(

ifp_numpy, c_init, a_init

)

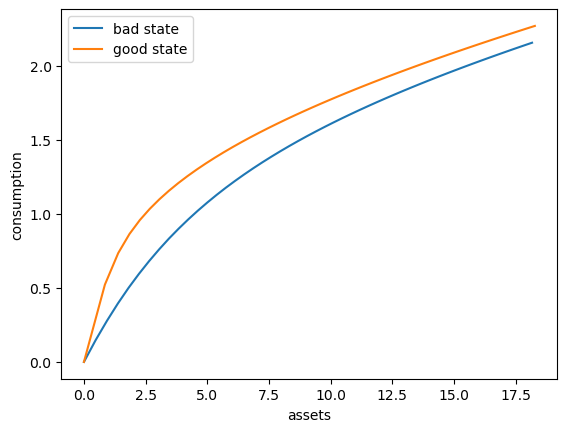

Here’s a plot of the optimal consumption policy for each \(z\) state

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

ax.plot(a_vec[:, 0], c_vec[:, 0], label='bad state')

ax.plot(a_vec[:, 1], c_vec[:, 1], label='good state')

ax.set(xlabel='assets', ylabel='consumption')

ax.legend()

plt.show()

62.4. JAX Implementation#

Now we write a more efficient JAX version, which can run on a GPU.

62.4.1. Set Up#

We start with a class called IFP that stores the model primitives.

class IFP(NamedTuple):

R: float # Gross interest rate R = 1 + r

β: float # Discount factor

γ: float # Preference parameter

Π: jnp.ndarray # Markov matrix for exogenous shock

z_grid: jnp.ndarray # Markov state values for Z_t

s: jnp.ndarray # Exogenous savings grid

a_y: float # Scale parameter for Y_t

b_y: float # Additive parameter for Y_t

η_draws: jnp.ndarray # Draws of innovation η for MC

def create_ifp(r=0.01,

β=0.94,

γ=1.5,

Π=((0.6, 0.4),

(0.05, 0.95)),

z_grid=(-10.0, jnp.log(2.0)),

savings_grid_max=16,

savings_grid_size=50,

a_y=0.2,

b_y=0.5,

shock_draw_size=100,

seed=1234):

key = jax.random.PRNGKey(seed)

s = jnp.linspace(0, savings_grid_max, savings_grid_size)

Π, z_grid = jnp.array(Π), jnp.array(z_grid)

R = 1 + r

η_draws = jax.random.normal(key, (shock_draw_size,))

assert R * β < 1, "Stability condition violated."

return IFP(R, β, γ, Π, z_grid, s, a_y, b_y, η_draws)

62.4.2. Solver#

Here is the operator \(K\) that transforms current guess \(\sigma\) into next period guess \(K\sigma\).

def K(

c_in: jnp.ndarray,

a_in: jnp.ndarray,

ifp: IFP

) -> jnp.ndarray:

"""

The Euler equation operator for the IFP model using the

Endogenous Grid Method.

This operator implements one iteration of the EGM algorithm to

update the consumption policy function.

"""

R, β, γ, Π, z_grid, s, a_y, b_y, η_draws = ifp

n_a = len(s)

n_z = len(z_grid)

# Utility functions

def u_prime(c):

return c**(-γ)

def u_prime_inv(c):

return c**(-1/γ)

def y(z, η):

return jnp.exp(a_y * η + z * b_y)

def compute_c(i, j):

" Compute c_ij when i >= 1 (interior choice). "

def expected_mu(k):

" Approximate ∫ u'(σ(R s_i + y(z_k, η'), z_k)) φ(η') dη' "

def compute_mu_at_eta(η):

" Compute u'(σ(R * s_i + y(z_k, η), z_k)) "

next_a = R * s[i] + y(z_grid[k], η)

# Interpolate to get σ(R * s_i + y(z_k, η), z_k)

next_c = jnp.interp(next_a, a_in[:, k], c_in[:, k])

# Return u'(σ(R * s_i + y(z_k, η), z_k))

return u_prime(next_c)

# Average over η draws to approximate the inner integral

# ∫ u'(σ(R s_i + y(z_k, η'), z_k)) φ(η') dη'

all_draws = jax.vmap(compute_mu_at_eta)(η_draws)

return jnp.mean(all_draws)

# Compute expectation: Σ_k [∫ u'(σ(...)) φ(η) dη] * Π[j, k]

expectations = jax.vmap(expected_mu)(jnp.arange(n_z))

expectation = jnp.sum(expectations * Π[j, :])

# Invert to get consumption c_ij at (s_i, z_j)

return u_prime_inv(β * R * expectation)

# Set up index grids for vmap computation of all c_{ij}

i_grid = jnp.arange(1, n_a)

j_grid = jnp.arange(n_z)

# vmap over j for each i

compute_c_i = jax.vmap(compute_c, in_axes=(None, 0))

# vmap over i

compute_c = jax.vmap(lambda i: compute_c_i(i, j_grid))

# Compute consumption for i >= 1

c_out_interior = compute_c(i_grid) # Shape: (n_a-1, n_z)

# For i = 0, set consumption to 0

c_out_boundary = jnp.zeros((1, n_z))

# Concatenate boundary and interior

c_out = jnp.concatenate([c_out_boundary, c_out_interior], axis=0)

# Compute endogenous asset grid: a^e_{ij} = c_{ij} + s_i

a_out = c_out + s[:, None]

return c_out, a_out

Here’s a jit-accelerated iterative routine to solve the model using this operator.

@jax.jit

def solve_model(

ifp: IFP,

c_init: jnp.ndarray, # Initial guess of σ on grid endogenous grid

a_init: jnp.ndarray, # Initial endogenous grid

tol: float = 1e-5,

max_iter: int = 1000

) -> jnp.ndarray:

"""

Solve the model using time iteration with EGM.

"""

def condition(loop_state):

c_in, a_in, i, error = loop_state

return (error > tol) & (i < max_iter)

def body(loop_state):

c_in, a_in, i, error = loop_state

c_out, a_out = K(c_in, a_in, ifp)

error = jnp.max(jnp.abs(c_out - c_in))

i += 1

return c_out, a_out, i, error

i, error = 0, tol + 1

initial_state = (c_init, a_init, i, error)

final_loop_state = jax.lax.while_loop(condition, body, initial_state)

c_out, a_out, i, error = final_loop_state

return c_out, a_out

62.4.3. Test run#

Let’s road test the EGM code.

ifp = create_ifp()

R, β, γ, Π, z_grid, s, a_y, b_y, η_draws = ifp

# Set initial conditions where the agent consumes everything

a_init = s[:, None] * jnp.ones(len(z_grid))

c_init = a_init

# Solve starting from these initial conditions

c_vec_jax, a_vec_jax = solve_model(ifp, c_init, a_init)

To verify the correctness of our JAX implementation, let’s compare it with the NumPy version we developed earlier.

# Compare the results

max_c_diff = np.max(np.abs(np.array(c_vec) - c_vec_jax))

max_ae_diff = np.max(np.abs(np.array(a_vec) - a_vec_jax))

print(f"Maximum difference in consumption policy: {max_c_diff:.2e}")

print(f"Maximum difference in asset grid: {max_ae_diff:.2e}")

Maximum difference in consumption policy: 3.94e-01

Maximum difference in asset grid: 3.94e-01

These numbers confirm that we are computing essentially the same policy using the two approaches.

(Remaining differences are mainly due to different Monte Carlo integration outcomes over relatively small samples.)

62.4.4. Timing#

Now let’s compare the execution time between NumPy and JAX implementations.

import time

# Set up initial conditions for NumPy version

s_np = np.array(s)

z_grid_np = np.array(z_grid)

a_init_np = s_np[:, None] * np.ones(len(z_grid_np))

c_init_np = a_init_np.copy()

# Set up initial conditions for JAX version

a_init_jx = s[:, None] * jnp.ones(len(z_grid))

c_init_jx = a_init_jx

# Time NumPy version

start = time.time()

c_vec_np, a_vec_np = solve_model_numpy(ifp_numpy, c_init_np, a_init_np)

numpy_time = time.time() - start

# Time JAX version (with compilation)

start = time.time()

c_vec_jx, a_vec_jx = solve_model(ifp, c_init_jx, a_init_jx)

c_vec_jx.block_until_ready()

jax_time_with_compile = time.time() - start

# Time JAX version (without compilation - second run)

start = time.time()

c_vec_jx, a_vec_jx = solve_model(ifp, c_init_jx, a_init_jx)

c_vec_jx.block_until_ready()

jax_time = time.time() - start

print(f"NumPy time: {numpy_time:.4f} seconds")

print(f"JAX time (with compile): {jax_time_with_compile:.4f} seconds")

print(f"JAX time (without compile): {jax_time:.4f} seconds")

print(f"Speedup (NumPy/JAX): {numpy_time/jax_time:.2f}x")

NumPy time: 0.3793 seconds

JAX time (with compile): 0.0098 seconds

JAX time (without compile): 0.0094 seconds

Speedup (NumPy/JAX): 40.45x

The JAX implementation is significantly faster due to JIT compilation and GPU/TPU acceleration (if available).

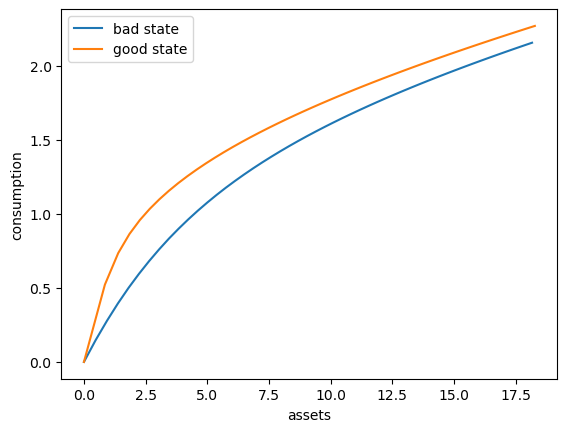

Here’s a plot of the optimal policy for each \(z\) state

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

ax.plot(a_vec[:, 0], c_vec[:, 0], label='bad state')

ax.plot(a_vec[:, 1], c_vec[:, 1], label='good state')

ax.set(xlabel='assets', ylabel='consumption')

ax.legend()

plt.show()

62.4.5. Dynamics#

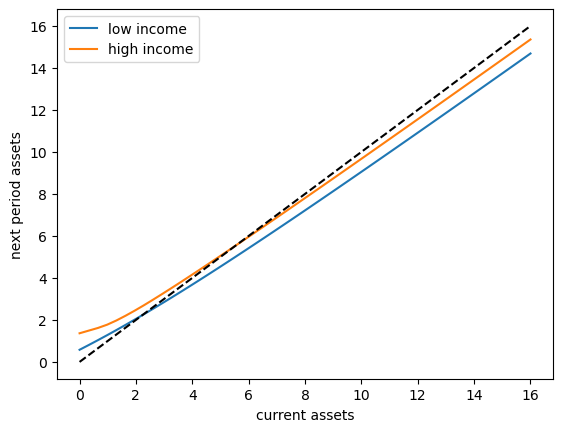

To begin to understand the long run asset levels held by households under the default parameters, let’s look at the 45 degree diagram showing the law of motion for assets under the optimal consumption policy.

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

def y(z, η):

return jnp.exp(a_y * η + z * b_y)

def y_bar(k):

"""

Taking z = z_grid[k], compute an approximation to

E_z Y' = Σ_{z'} ∫ y(z', η') φ(η') dη' Π[z, z']

This is the expectation of Y_{t+1} given Z_t = z.

"""

# Approximate ∫ y(z', η') φ(η') dη' at given z'

def mean_y_at_z(z_prime):

return jnp.mean(y(z_prime, η_draws))

# Evaluate this integral across all z'

y_means = jax.vmap(mean_y_at_z)(z_grid)

# Weight by transition probabilities and sum

return jnp.sum(y_means * Π[k, :])

for k, label in zip((0, 1), ('low income', 'high income')):

# Interpolate consumption policy on the savings grid

c_on_grid = jnp.interp(s, a_vec[:, k], c_vec[:, k])

ax.plot(s, R * (s - c_on_grid) + y_bar(k) , label=label)

ax.plot(s, s, 'k--')

ax.set(xlabel='current assets', ylabel='next period assets')

ax.legend()

plt.show()

The unbroken lines show the update function for assets at each \(z\), which is

where

is a Monte Carlo approximation to expected labor income conditional on current state \(z\).

The dashed line is the 45 degree line.

The figure suggests that, on average, the dynamics will be stable — assets do not diverge even in the highest state.

This turns out to be true: there is a unique stationary distribution of assets.

For details see [Ma et al., 2020]

This stationary distribution represents the long run dispersion of assets across households when households have idiosyncratic shocks.

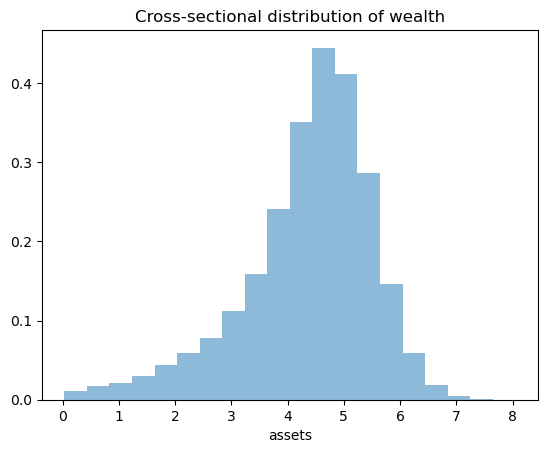

62.5. Simulation#

Let’s return to the default model and study the stationary distribution of assets.

Our plan is to run a large number of households forward for \(T\) periods and then histogram the cross-sectional distribution of assets.

Set num_households=50_000, T=500.

First we write a function to run a single household forward in time and record the final value of assets.

The function takes a solution pair c_vec and a_vec, understanding them

as representing an optimal policy associated with a given model ifp

@jax.jit

def simulate_household(

key, a_0, z_idx_0, c_vec, a_vec, ifp, T

):

"""

Simulates a single household for T periods to approximate the stationary

distribution of assets.

- key is the state of the random number generator

- ifp is an instance of IFP

- c_vec, a_vec are the optimal consumption policy, endogenous grid for ifp

"""

R, β, γ, Π, z_grid, s, a_y, b_y, η_draws = ifp

n_z = len(z_grid)

def y(z, η):

return jnp.exp(a_y * η + z * b_y)

# Create interpolation function for consumption policy

σ = lambda a, z_idx: jnp.interp(a, a_vec[:, z_idx], c_vec[:, z_idx])

# Simulate forward T periods

def update(t, state):

a, z_idx = state

# Draw next shock z' from Π[z, z']

current_key = jax.random.fold_in(key, 2*t)

z_next_idx = jax.random.choice(current_key, n_z, p=Π[z_idx]).astype(jnp.int32)

z_next = z_grid[z_next_idx]

# Draw η shock

η_key = jax.random.fold_in(key, 2*t + 1)

η = jax.random.normal(η_key)

# Update assets: a' = R * (a - c) + Y'

a_next = R * (a - σ(a, z_idx)) + y(z_next, η)

# Return updated state

return a_next, z_next_idx

initial_state = a_0, z_idx_0

final_state = jax.lax.fori_loop(0, T, update, initial_state)

a_final, _ = final_state

return a_final

Now we write a function to simulate many households in parallel.

def compute_asset_stationary(

c_vec, a_vec, ifp, num_households=50_000, T=500, seed=1234

):

"""

Simulates num_households households for T periods to approximate

the stationary distribution of assets.

Returns the final cross-section of asset holdings.

- ifp is an instance of IFP

- c_vec, a_vec are the optimal consumption policy and endogenous grid.

"""

R, β, γ, Π, z_grid, s, a_y, b_y, η_draws = ifp

n_z = len(z_grid)

# Create interpolation function for consumption policy

# Interpolate on the endogenous grid

σ = lambda a, z_idx: jnp.interp(a, a_vec[:, z_idx], c_vec[:, z_idx])

# Start with assets = savings_grid_max / 2

a_0_vector = jnp.full(num_households, s[-1] / 2)

# Initialize the exogenous state of each household

z_idx_0_vector = jnp.zeros(num_households).astype(jnp.int32)

# Vectorize over many households

key = jax.random.PRNGKey(seed)

keys = jax.random.split(key, num_households)

# Vectorize simulate_household in (key, a_0, z_idx_0)

sim_all_households = jax.vmap(

simulate_household, in_axes=(0, 0, 0, None, None, None, None)

)

assets = sim_all_households(keys, a_0_vector, z_idx_0_vector, c_vec, a_vec, ifp, T)

return np.array(assets)

Now we call the function, generate the asset distribution and histogram it:

ifp = create_ifp()

R, β, γ, Π, z_grid, s, a_y, b_y, η_draws = ifp

a_init = s[:, None] * jnp.ones(len(z_grid))

c_init = a_init

c_vec, a_vec = solve_model(ifp, c_init, a_init)

assets = compute_asset_stationary(c_vec, a_vec, ifp)

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

ax.hist(assets, bins=20, alpha=0.5, density=True)

ax.set(xlabel='assets', title="Cross-sectional distribution of wealth")

plt.show()

As was the case in The Income Fluctuation Problem III: The Endogenous Grid Method, the wealth distribution looks implausible.

While we have at least gained a nontrivial right tail, we still have a left skew.

62.6. Wealth Inequality#

Lets’ look at wealth inequality by computing some standard measures of this phenomenon.

We will also examine how inequality varies with the interest rate.

62.6.1. Measuring Inequality#

We’ll compute two common measures of wealth inequality:

Gini coefficient: A measure of inequality ranging from 0 (perfect equality) to 1 (perfect inequality)

Top 1% wealth share: The fraction of total wealth held by the richest 1% of households

Here are functions to compute these measures:

def gini_coefficient(x):

"""

Compute the Gini coefficient for array x.

"""

x = jnp.asarray(x)

n = len(x)

x_sorted = jnp.sort(x)

# Compute Gini coefficient

cumsum = jnp.cumsum(x_sorted)

a = (2 * jnp.sum((jnp.arange(1, n+1)) * x_sorted)) / (n * cumsum[-1])

return a - (n + 1) / n

def top_share(

x: jnp.array, # array of wealth values

p: float=0.01 # fraction of top households (default 0.01 for top 1%)

):

"""

Compute the share of total wealth held by the top p fraction of households.

"""

x = jnp.asarray(x)

x_sorted = jnp.sort(x)

# Number of households in top p%

n_top = int(jnp.ceil(len(x) * p))

# Wealth held by top p%

wealth_top = jnp.sum(x_sorted[-n_top:])

# Total wealth

wealth_total = jnp.sum(x_sorted)

return wealth_top / wealth_total

Let’s compute these measures for our baseline simulation:

gini = gini_coefficient(assets)

top1 = top_share(assets, p=0.01)

print(f"Gini coefficient: {gini:.4f}")

print(f"Top 1% wealth share: {top1:.4f}")

Gini coefficient: 0.1428

Top 1% wealth share: 0.0154

These numbers are a long way out, at least for a country such as the US!

Recent numbers suggest that

the Gini coefficient for wealth in the US is around 0.8

the top 1% wealth share is over 0.3

Of course we have not made much effort to accurately estimate or calibrate our parameters.

But actually the cause is deeper — a model with this structure will always struggle to replicate the observed wealth distribution.

In a later lecture we’ll see if we can improve on these numbers.

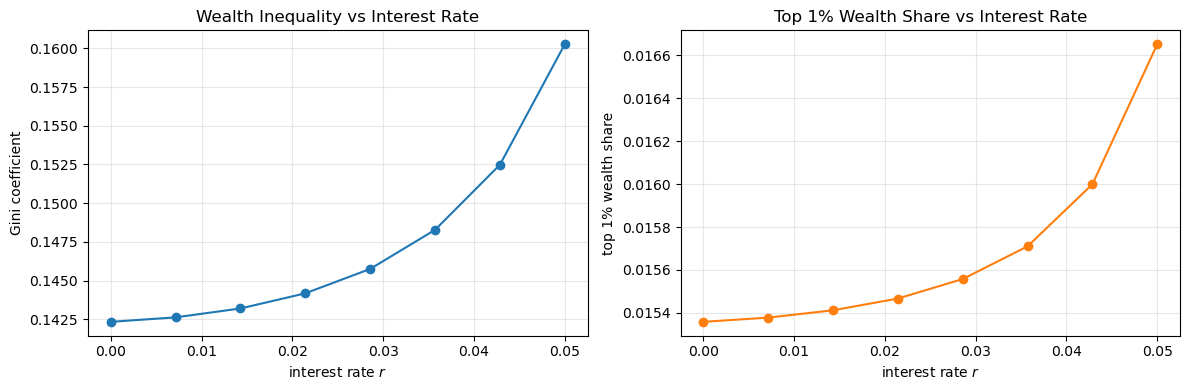

62.6.2. Interest Rate and Inequality#

Let’s examine how wealth inequality varies with the interest rate \(r\).

We conjecture that higher interest rates will increase wealth inequality, as wealthier households benefit more from returns on their assets.

Let’s investigate empirically:

# Test over 8 interest rate values

M = 8

r_vals = np.linspace(0, 0.05, M)

gini_vals = []

top1_vals = []

# Solve and simulate for each r

for r in r_vals:

print(f'Analyzing inequality at r = {r:.4f}')

ifp = create_ifp(r=r)

R, β, γ, Π, z_grid, s, a_y, b_y, η_draws = ifp

a_init = s[:, None] * jnp.ones(len(z_grid))

c_init = a_init

c_vec, a_vec = solve_model(ifp, c_init, a_init)

assets = compute_asset_stationary(

c_vec, a_vec, ifp, num_households=50_000, T=500

)

gini = gini_coefficient(assets)

top1 = top_share(assets, p=0.01)

gini_vals.append(gini)

top1_vals.append(top1)

# Use last solution as initial conditions for the policy solver

c_init = c_vec

a_init = a_vec

Analyzing inequality at r = 0.0000

Analyzing inequality at r = 0.0071

Analyzing inequality at r = 0.0143

Analyzing inequality at r = 0.0214

Analyzing inequality at r = 0.0286

Analyzing inequality at r = 0.0357

Analyzing inequality at r = 0.0429

Analyzing inequality at r = 0.0500

Now let’s visualize the results:

fig, axes = plt.subplots(1, 2, figsize=(12, 4))

# Plot Gini coefficient vs interest rate

axes[0].plot(r_vals, gini_vals, 'o-')

axes[0].set_xlabel('interest rate $r$')

axes[0].set_ylabel('Gini coefficient')

axes[0].set_title('Wealth Inequality vs Interest Rate')

axes[0].grid(alpha=0.3)

# Plot top 1% share vs interest rate

axes[1].plot(r_vals, top1_vals, 'o-', color='C1')

axes[1].set_xlabel('interest rate $r$')

axes[1].set_ylabel('top 1% wealth share')

axes[1].set_title('Top 1% Wealth Share vs Interest Rate')

axes[1].grid(alpha=0.3)

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

The results show that these two inequality measures increase with the interest rate.

However the differences are minor and we cannot increase \(r\) much more without violating the stability constraint.

Certainly changing the interest rate cannot produce the kinds of numbers that we see in the data.

62.7. Exercises#

Exercise 62.1

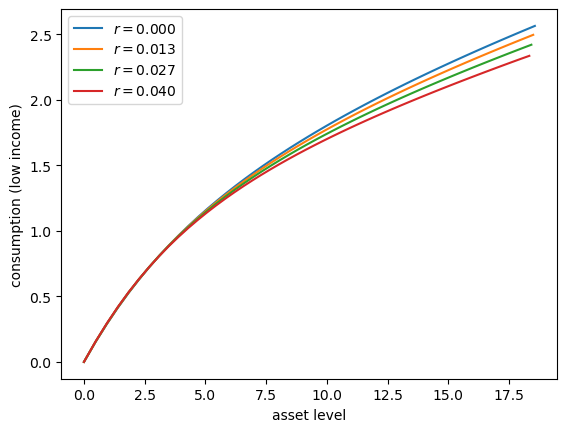

Let’s consider how the interest rate affects consumption.

Step

rthroughnp.linspace(0, 0.016, 4).Other than

r, hold all parameters at their default values.Plot consumption against assets for income shock fixed at the smallest value.

Your figure should show that, for this model, higher interest rates suppress consumption (because they encourage more savings).

Solution

Here’s one solution:

# With β=0.96, we need R*β < 1, so r < 0.0416

r_vals = np.linspace(0, 0.04, 4)

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

for r_val in r_vals:

ifp = create_ifp(r=r_val)

R, β, γ, Π, z_grid, s, a_y, b_y, η_draws = ifp

a_init = s[:, None] * jnp.ones(len(z_grid))

c_init = a_init

c_vec, a_vec = solve_model(ifp, c_init, a_init)

# Plot policy

ax.plot(a_vec[:, 0], c_vec[:, 0], label=f'$r = {r_val:.3f}$')

# Start next round with last solution

c_init = c_vec

a_init = a_vec

ax.set(xlabel='asset level', ylabel='consumption (low income)')

ax.legend()

plt.show()

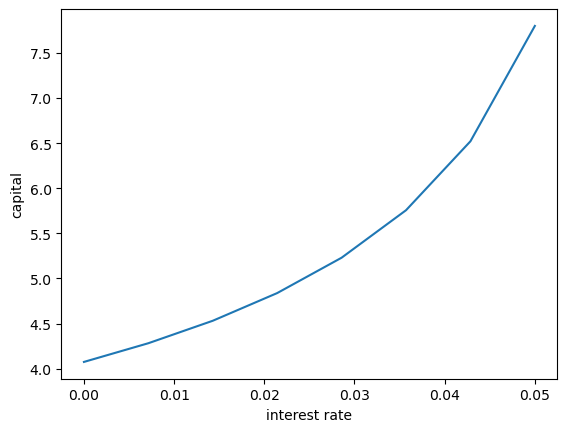

Exercise 62.2

Following on from Exercises 1, let’s look at how savings and aggregate asset holdings vary with the interest rate

Note

[Ljungqvist and Sargent, 2018] section 18.6 can be consulted for more background on the topic treated in this exercise.

For a given parameterization of the model, the mean of the stationary distribution of assets can be interpreted as aggregate capital in an economy with a unit mass of ex-ante identical households facing idiosyncratic shocks.

Your task is to investigate how this measure of aggregate capital varies with the interest rate.

Intuition suggests that a higher interest rate should encourage capital formation — test this.

For the interest rate grid, use

M = 8

r_vals = np.linspace(0, 0.05, M)

Solution

Here’s one solution

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

asset_mean = []

for r in r_vals:

print(f'Solving model at r = {r}')

ifp = create_ifp(r=r)

R, β, γ, Π, z_grid, s, a_y, b_y, η_draws = ifp

a_init = s[:, None] * jnp.ones(len(z_grid))

c_init = a_init

c_vec, a_vec = solve_model(ifp, c_init, a_init)

assets = compute_asset_stationary(

c_vec, a_vec, ifp, num_households=10_000, T=500

)

mean = np.mean(assets)

asset_mean.append(mean)

print(f' Mean assets: {mean:.4f}')

# Start next round with last solution

c_init = c_vec

a_init = a_vec

ax.plot(r_vals, asset_mean)

ax.set(xlabel='interest rate', ylabel='capital')

plt.show()

Solving model at r = 0.0

Mean assets: 4.0748

Solving model at r = 0.0071428571428571435

Mean assets: 4.2822

Solving model at r = 0.014285714285714287

Mean assets: 4.5313

Solving model at r = 0.02142857142857143

Mean assets: 4.8383

Solving model at r = 0.028571428571428574

Mean assets: 5.2304

Solving model at r = 0.03571428571428572

Mean assets: 5.7570

Solving model at r = 0.04285714285714286

Mean assets: 6.5214

Solving model at r = 0.05

Mean assets: 7.8005

As expected, aggregate savings increases with the interest rate.