92. First-Price and Second-Price Auctions#

This lecture is designed to set the stage for a subsequent lecture about Multiple Good Allocation Mechanisms

In that lecture, a planner or auctioneer simultaneously allocates several goods to set of people.

In the present lecture, a single good is allocated to one person within a set of people.

Here we’ll learn about and simulate two classic auctions :

a First-Price Sealed-Bid Auction (FPSB)

a Second-Price Sealed-Bid Auction (SPSB) created by William Vickrey [Vickrey, 1961]

We’ll also learn about and apply a

Revenue Equivalent Theorem

We recommend watching this video about second price auctions by Anders Munk-Nielsen:

and

Anders Munk-Nielsen put his code on GitHub.

Much of our Python code below is based on his.

92.1. First-price sealed-bid auction (FPSB)#

Protocols:

A single good is auctioned.

Prospective buyers simultaneously submit sealed bids.

Each bidder knows only his/her own bid.

The good is allocated to the person who submits the highest bid.

The winning bidder pays price she has bid.

Detailed Setting:

There are \(n>2\) prospective buyers named \(i = 1, 2, \ldots, n\).

Buyer \(i\) attaches value \(v_i\) to the good being sold.

Buyer \(i\) wants to maximize the expected value of her surplus defined as \(v_i - p\), where \(p\) is the price that she pays, conditional on her winning the auction.

Evidently,

If \(i\) bids exactly \(v_i\), she pays what she thinks it is worth and gathers no surplus value.

Buyer \(i\) will never want to bid more than \(v_i\).

If buyer \(i\) bids \(b < v_i\) and wins the auction, then she gathers surplus value \(v_i - b > 0\).

If buyer \(i\) bids \(b < v_i\) and someone else bids more than \(b\), buyer \(i\) loses the auction and gets no surplus value.

To proceed, buyer \(i\) wants to know the probability that she wins the auction as a function of her bid \(v_i\)

this requires that she know a probability distribution of bids \(v_j\) made by prospective buyers \(j \neq i\)

Given her idea about that probability distribution, buyer \(i\) wants to set a bid that maximizes the mathematical expectation of her surplus value.

Bids are sealed, so no bidder knows bids submitted by other prospective buyers.

This means that bidders are in effect participating in a game in which players do not know payoffs of other players.

This is a Bayesian game, a Nash equilibrium of which is called a Bayesian Nash equilibrium.

To complete the specification of the situation, we’ll assume that prospective buyers’ valuations are independently and identically distributed according to a probability distribution that is known by all bidders.

Bidder optimally chooses to bid less than \(v_i\).

92.1.1. Characterization of FPSB auction#

A FPSB auction has a unique symmetric Bayesian Nash Equilibrium.

The optimal bid of buyer \(i\) is

where \(v_{i}\) is the valuation of bidder \(i\) and \(y_{i}\) is the maximum valuation of all other bidders:

A proof for this assertion is available at the Wikipedia page about Vickrey auctions

92.2. Second-price sealed-bid auction (SPSB)#

Protocols: In a second-price sealed-bid (SPSB) auction, the winner pays the second-highest bid.

92.3. Characterization of SPSB auction#

In a SPSB auction bidders optimally choose to bid their values.

Formally, a dominant strategy profile in a SPSB auction with a single, indivisible item has each bidder bidding its value.

A proof is provided at the Wikipedia page about Vickrey auctions

92.4. Uniform distribution of private values#

We assume valuation \(v_{i}\) of bidder \(i\) is distributed \(v_{i} \stackrel{\text{i.i.d.}}{\sim} U(0,1)\).

Under this assumption, we can analytically compute probability distributions of prices bid in both FPSB and SPSB.

We’ll simulate outcomes and, by using a law of large numbers, verify that the simulated outcomes agree with analytical ones.

We can use our simulation to illustrate a Revenue Equivalence Theorem that asserts that on average first-price and second-price sealed bid auctions provide a seller the same revenue.

To read about the revenue equivalence theorem, see this Wikepedia page

92.5. Setup#

There are \(n\) bidders.

Each bidder knows that there are \(n-1\) other bidders.

92.6. First price sealed bid auction#

An optimal bid for bidder \(i\) in a FPSB is described by equations (92.1) and (92.2).

When bids are i.i.d. draws from a uniform distribution, the CDF of \(y_{i}\) is

and the PDF of \(y_i\) is \(\tilde{f}_{n-1}(y) = (n-1)y^{n-2}\).

Then bidder \(i\)’s optimal bid in a FPSB auction is:

92.7. Second price sealed bid auction#

In a SPSB, it is optimal for bidder \(i\) to bid \(v_i\).

92.8. Python code#

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import seaborn as sns

import scipy.stats as stats

import scipy.interpolate as interp

# for plots

plt.rcParams.update({"text.usetex": True, 'font.size': 14})

colors = plt.rcParams['axes.prop_cycle'].by_key()['color']

# ensure the notebook generates the same randomness

np.random.seed(1337)

We repeat an auction with 5 bidders for 100,000 times.

The valuations of each bidder is distributed \(U(0,1)\).

N = 5

R = 100_000

v = np.random.uniform(0, 1, (N, R))

# BNE in first-price sealed bid

b_star = lambda vi, N: ((N-1)/N) * vi

b = b_star(v,N)

We compute and sort bid price distributions that emerge under both FPSB and SPSB.

# Bidders' values are sorted in ascending order in each auction.

# We record the order because we want to apply it to bid price and their id.

idx = np.argsort(v, axis=0)

# same as np.sort(v, axis=0), except now we retain the idx

v = np.take_along_axis(v, idx, axis=0)

b = np.take_along_axis(b, idx, axis=0)

# the id for the bidders is created.

ii = np.repeat(np.arange(1, N+1)[:, None], R, axis=1)

# the id is sorted according to bid price as well.

ii = np.take_along_axis(ii, idx, axis=0)

# In FPSB and SPSB, winners are those with highest values.

winning_player = ii[-1, :]

# highest bid

winner_pays_fpsb = b[-1, :]

# 2nd-highest valuation

winner_pays_spsb = v[-2, :]

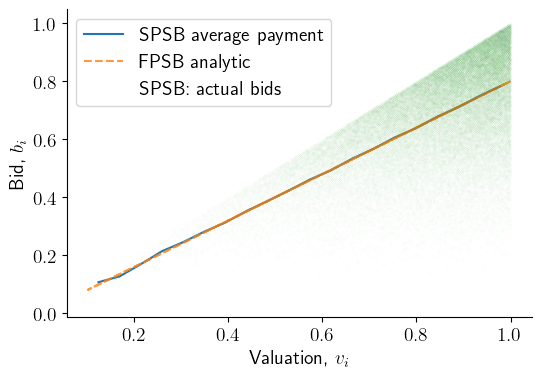

Let’s now plot the winning bids \(b_{(n)}\) (i.e. the payment) against valuations, \(v_{(n)}\) for both FPSB and SPSB.

Note that

FPSB: There is a unique bid corresponding to each valuation

SPSB: Because it equals the valuation of a second-highest bidder, what a winner pays varies even holding fixed the winner’s valuation. So here there is a frequency distribution of payments for each valuation.

# We intend to compute average payments of different groups of bidders

binned = stats.binned_statistic(v[-1, :], v[-2, :], statistic='mean', bins=20)

xx = binned.bin_edges

xx = [(xx[ii]+xx[ii+1])/2 for ii in range(len(xx)-1)]

yy = binned.statistic

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(6, 4))

ax.plot(xx, yy, label='SPSB average payment')

ax.plot(v[-1, :], b[-1, :], '--', alpha=0.8, label='FPSB analytic')

ax.plot(v[-1, :], v[-2, :], 'o', alpha=0.05,

markersize=0.1, label='SPSB: actual bids')

ax.legend(loc='best')

ax.set_xlabel('Valuation, $v_i$')

ax.set_ylabel('Bid, $b_i$')

sns.despine()

92.9. Revenue equivalence theorem#

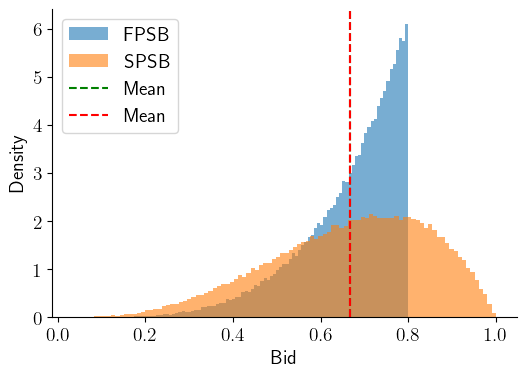

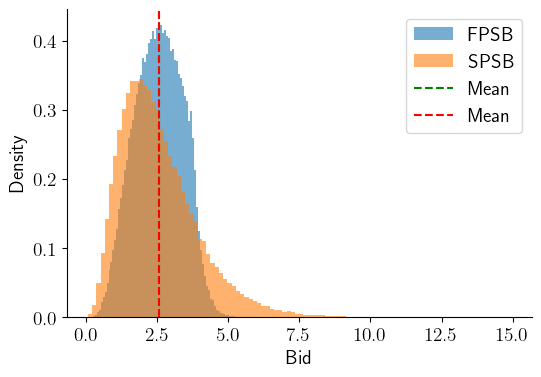

We now compare FPSB and a SPSB auctions from the point of view of the revenues that a seller can expect to acquire.

Expected Revenue FPSB:

The winner with valuation \(y\) pays \(\frac{n-1}{n}*y\), where n is the number of bidders.

Above we computed that the CDF is \(F_{n}(y) = y^{n}\) and the PDF is \(f_{n} = ny^{n-1}\).

Consequently, expected revenue is

Expected Revenue SPSB:

The expected revenue equals n \(\times\) expected payment of a bidder.

Computing this we get

Thus, while probability distributions of winning bids typically differ across the two types of auction, we deduce that expected payments are identical in FPSB and SPSB.

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(6, 4))

for payment, label in zip([winner_pays_fpsb, winner_pays_spsb], ['FPSB', 'SPSB']):

print('The average payment of %s: %.4f. Std.: %.4f. Median: %.4f' % (

label, payment.mean(), payment.std(), np.median(payment)))

ax.hist(payment, density=True, alpha=0.6, label=label, bins=100)

ax.axvline(winner_pays_fpsb.mean(), ls='--', c='g', label='Mean')

ax.axvline(winner_pays_spsb.mean(), ls='--', c='r', label='Mean')

ax.legend(loc='best')

ax.set_xlabel('Bid')

ax.set_ylabel('Density')

sns.despine()

The average payment of FPSB: 0.6665. Std.: 0.1129. Median: 0.6967

The average payment of SPSB: 0.6667. Std.: 0.1782. Median: 0.6862

Auction: Sealed-Bid |

First-Price |

Second-Price |

|---|---|---|

Winner |

Agent with highest bid |

Agent with highest bid |

Winner pays |

Winner’s bid |

Second-highest bid |

Loser pays |

0 |

0 |

Dominant strategy |

No dominant strategy |

Bidding truthfully is dominant strategy |

Bayesian Nash equilibrium |

Bidder \(i\) bids \(\frac{n-1}{n}v_{i}\) |

Bidder \(i\) truthfully bids \(v_{i}\) |

Auctioneer’s revenue |

\(\frac {n-1}{n+1}\) |

\(\frac {n-1}{n+1}\) |

Detour: Computing a Bayesian Nash Equibrium for FPSB

The Revenue Equivalence Theorem lets us find an optimal bidding strategy for a FPSB auction from outcomes of a SPSB auction.

Let \(b(v_{i})\) be the optimal bid in a FPSB auction.

The revenue equivalence theorem tells us that a bidder agent with value \(v_{i}\) on average receives the same payment in the two types of auction.

Consequently,

It follows that an optimal bidding strategy in a FPSB auction is \(b(v_{i}) = \mathbf{E}_{y_{i}}[y_{i} | y_{i} < v_{i}]\).

92.10. Calculation of bid price in FPSB#

In equations (92.1) and (92.2), we displayed formulas for optimal bids in a symmetric Bayesian Nash Equilibrium of a FPSB auction.

where

\(v_{i} = \) value of bidder \(i\)

\(y_{i} = \): maximum value of all bidders except \(i\), i.e., \(y_{i} = \max_{j \neq i} v_{j}\)

Above, we computed an optimal bid price in a FPSB auction analytically for a case in which private values are uniformly distributed.

For most probability distributions of private values, analytical solutions aren’t easy to compute.

Instead, we can compute bid prices in FPSB auctions numerically as functions of the distribution of private values.

def evaluate_largest(v_hat, array, order=1):

"""

A method to estimate the largest (or certain-order largest) value of the other biders,

conditional on player 1 wins the auction.

Parameters:

----------

v_hat : float, the value of player 1. The biggest value in the auction that player 1 wins.

array: 2 dimensional array of bidders' values in shape of (N,R),

where N: number of players, R: number of auctions

order: int. The order of largest number among bidders who lose.

e.g. the order for largest number beside winner is 1.

the order for second-largest number beside winner is 2.

"""

N, R = array.shape

# drop the first row because we assume first row is the winner's bid

array_residual = array[1:, :].copy()

winning_auctions_mask = (array_residual < v_hat).all(axis=0)

num_winning_auctions = np.sum(winning_auctions_mask)

if num_winning_auctions == 0:

return np.nan

array_conditional = array_residual[:, winning_auctions_mask]

array_conditional_sorted = np.sort(array_conditional, axis=0)

order_largest_bids = array_conditional_sorted[-order, :]

return np.mean(order_largest_bids)

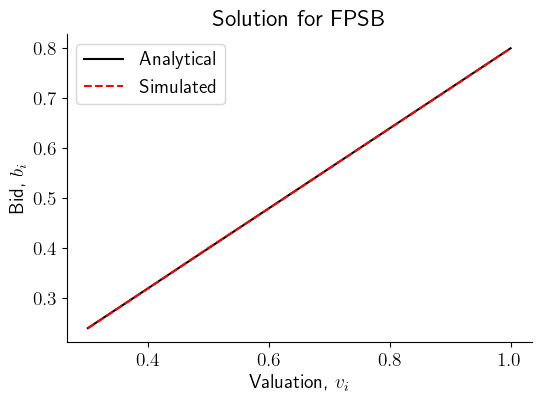

We can check the accuracy of our evaluate_largest method by comparing it with an analytical solution.

We find that the evaluate_largest method functions well

v_grid = np.linspace(0.3, 1, 8)

bid_analytical = b_star(v_grid, N)

# Redraw valuations

v = np.random.uniform(0, 1, (N, R))

bid_simulated = [evaluate_largest(ii, v) for ii in v_grid]

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(6, 4))

ax.plot(v_grid, bid_analytical, '-', color='k', label='Analytical')

ax.plot(v_grid, bid_simulated, '--', color='r', label='Simulated')

ax.legend(loc='best')

ax.set_xlabel('Valuation, $v_i$')

ax.set_ylabel('Bid, $b_i$')

ax.set_title('Solution for FPSB')

sns.despine()

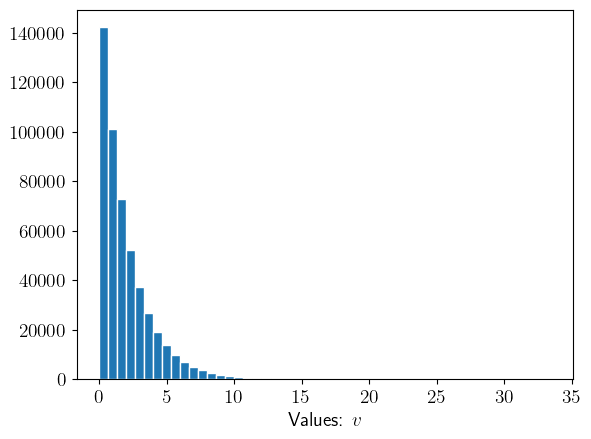

92.11. \(\chi^2\) Distribution#

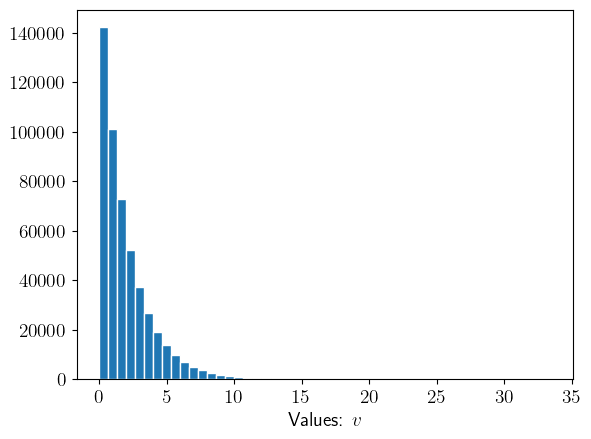

Let’s try an example in which the distribution of private values is a \(\chi^2\) distribution.

We’ll start by taking a look at a \(\chi^2\) distribution with the help of the following Python code:

np.random.seed(1337)

v = np.random.chisquare(df=2, size=(N * R,))

plt.hist(v, bins=50, edgecolor='w')

plt.xlabel('Values: $v$')

plt.show()

Now we’ll get Python to construct a bid price function

np.random.seed(1337)

v = np.random.chisquare(df=2, size=(N, R))

# we compute the quantile of v as our grid

pct_quantile = np.linspace(0, 100, 101)[1:-1]

v_grid = np.percentile(v.flatten(), q=pct_quantile)

# nan values are returned for some low quantiles due to lack of observations

EV = [evaluate_largest(ii, v) for ii in v_grid]

# we insert 0 into our grid and bid price function as a complement

EV = np.insert(EV, 0, 0)

v_grid = np.insert(v_grid, 0, 0)

b_star_num = interp.interp1d(v_grid, EV, fill_value="extrapolate")

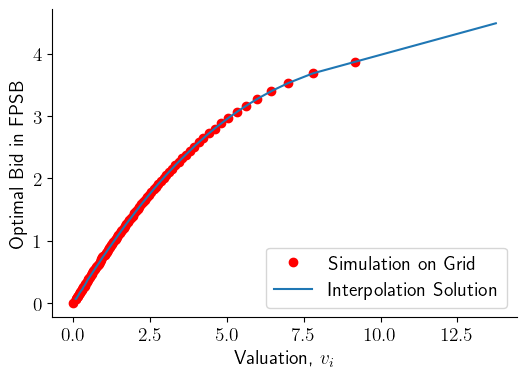

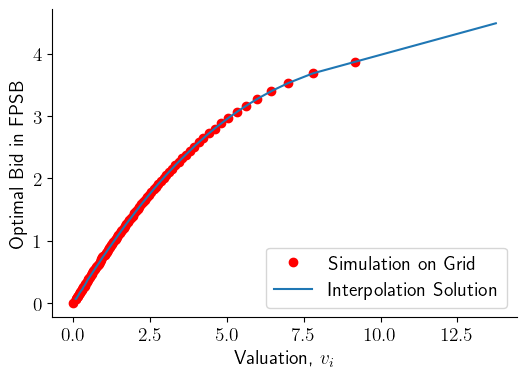

We check our bid price function by computing and visualizing the result.

pct_quantile_fine = np.linspace(0, 100, 1001)[1:-1]

v_grid_fine = np.percentile(v.flatten(), q=pct_quantile_fine)

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(6, 4))

ax.plot(v_grid, EV, 'or', label='Simulation on Grid')

ax.plot(v_grid_fine, b_star_num(v_grid_fine),

'-', label='Interpolation Solution')

ax.legend(loc='best')

ax.set_xlabel('Valuation, $v_i$')

ax.set_ylabel('Optimal Bid in FPSB')

sns.despine()

Now we can use Python to compute the probability distribution of the price paid by the winning bidder

b = b_star_num(v)

idx = np.argsort(v, axis=0)

# same as np.sort(v, axis=0), except now we retain the idx

v = np.take_along_axis(v, idx, axis=0)

b = np.take_along_axis(b, idx, axis=0)

ii = np.repeat(np.arange(1, N + 1)[:, None], R, axis=1)

ii = np.take_along_axis(ii, idx, axis=0)

winning_player = ii[-1, :]

# highest bid

winner_pays_fpsb = b[-1, :]

# 2nd-highest valuation

winner_pays_spsb = v[-2, :]

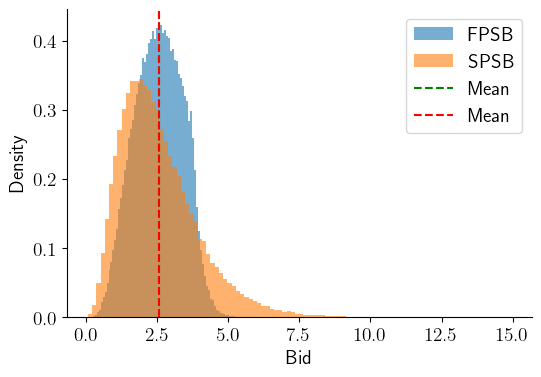

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(6, 4))

for payment, label in zip([winner_pays_fpsb, winner_pays_spsb],

['FPSB', 'SPSB']):

print('The average payment of %s: %.4f. Std.: %.4f. Median: %.4f' % (

label, payment.mean(), payment.std(), np.median(payment)))

ax.hist(payment, density=True, alpha=0.6, label=label, bins=100)

ax.axvline(winner_pays_fpsb.mean(), ls='--', c='g', label='Mean')

ax.axvline(winner_pays_spsb.mean(), ls='--', c='r', label='Mean')

ax.legend(loc='best')

ax.set_xlabel('Bid')

ax.set_ylabel('Density')

sns.despine()

The average payment of FPSB: 2.5693. Std.: 0.8383. Median: 2.5829

The average payment of SPSB: 2.5661. Std.: 1.3580. Median: 2.3180

92.12. Code summary#

We assemble the functions that we have used into a Python class

class bid_price_solution:

def __init__(self, array):

"""

A class that can plot the value distribution of bidders,

compute the optimal bid price for bidders in FPSB

and plot the distribution of winner's payment in both FPSB and SPSB

Parameters:

----------

array: 2 dimensional array of bidders' values in shape of (N, R),

where N: number of players, R: number of auctions

"""

self.value_mat = array.copy()

return None

def plot_value_distribution(self):

plt.hist(self.value_mat.flatten(), bins=50, edgecolor='w')

plt.xlabel('Values: $v$')

plt.show()

return None

def evaluate_largest(self, v_hat, order=1):

N, R = self.value_mat.shape

# drop the first row because we assume first row is the winner's bid

array_residual = self.value_mat[1:, :].copy()

winning_auctions_mask = (array_residual < v_hat).all(axis=0)

num_winning_auctions = np.sum(winning_auctions_mask)

if num_winning_auctions == 0:

return np.nan

array_conditional = array_residual[:, winning_auctions_mask]

array_conditional_sorted = np.sort(array_conditional, axis=0)

order_largest_bids = array_conditional_sorted[-order, :]

return np.mean(order_largest_bids)

def compute_optimal_bid_FPSB(self):

# we compute the quantile of v as our grid

pct_quantile = np.linspace(0, 100, 101)[1:-1]

v_grid = np.percentile(self.value_mat.flatten(), q=pct_quantile)

# nan values are returned for some low quantiles due to lack of observations

EV = [self.evaluate_largest(ii) for ii in v_grid]

# we insert 0 into our grid and bid price function as a complement

EV = np.insert(EV, 0, 0)

v_grid = np.insert(v_grid, 0, 0)

self.b_star_num = interp.interp1d(v_grid, EV,

fill_value="extrapolate")

pct_quantile_fine = np.linspace(0, 100, 1001)[1:-1]

v_grid_fine = np.percentile(self.value_mat.flatten(),

q=pct_quantile_fine)

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(6, 4))

ax.plot(v_grid, EV, 'or', label='Simulation on Grid')

ax.plot(v_grid_fine, self.b_star_num(v_grid_fine),

'-', label='Interpolation Solution')

ax.legend(loc='best')

ax.set_xlabel('Valuation, $v_i$')

ax.set_ylabel('Optimal Bid in FPSB')

sns.despine()

return None

def plot_winner_payment_distribution(self):

self.b = self.b_star_num(self.value_mat)

idx = np.argsort(self.value_mat, axis=0)

# same as np.sort(v, axis=0), except now we retain the idx

self.v = np.take_along_axis(self.value_mat, idx, axis=0)

self.b = np.take_along_axis(self.b, idx, axis=0)

N, R = self.value_mat.shape

self.ii = np.repeat(np.arange(1, N + 1)[:, None], R, axis=1)

self.ii = np.take_along_axis(self.ii, idx, axis=0)

winning_player = self.ii[-1, :]

# highest bid

winner_pays_fpsb = self.b[-1, :]

# 2nd-highest valuation

winner_pays_spsb = self.v[-2, :]

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(6, 4))

for payment, label in zip([winner_pays_fpsb, winner_pays_spsb],

['FPSB', 'SPSB']):

print('The average payment of %s: %.4f. Std.: %.4f. Median: %.4f' %

(label, payment.mean(), payment.std(), np.median(payment)))

ax.hist(payment, density=True, alpha=0.6, label=label, bins=100)

ax.axvline(winner_pays_fpsb.mean(), ls='--', c='g', label='Mean')

ax.axvline(winner_pays_spsb.mean(), ls='--', c='r', label='Mean')

ax.legend(loc='best')

ax.set_xlabel('Bid')

ax.set_ylabel('Density')

sns.despine()

return None

np.random.seed(1337)

v = np.random.chisquare(df=2, size=(N, R))

chi_squ_case = bid_price_solution(v)

chi_squ_case.plot_value_distribution()

chi_squ_case.compute_optimal_bid_FPSB()

chi_squ_case.plot_winner_payment_distribution()

The average payment of FPSB: 2.5693. Std.: 0.8383. Median: 2.5829

The average payment of SPSB: 2.5661. Std.: 1.3580. Median: 2.3180

92.13. References#

Wikipedia for FPSB: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/First-price_sealed-bid_auction

Wikipedia for SPSB: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vickrey_auction

Chandra Chekuri’s lecture note for algorithmic game theory: https://chekuri.cs.illinois.edu/teaching/spring2008/Lectures/scribed/Notes20.pdf

Tim Salmon. ECO 4400 Supplemental Handout: All About Auctions: https://s2.smu.edu/tsalmon/auctions.pdf

Auction Theory- Revenue Equivalence Theorem: https://michaellevet.wordpress.com/2015/07/06/auction-theory-revenue-equivalence-theorem/

Order Statistics: https://online.stat.psu.edu/stat415/book/export/html/834